Every year, hundreds of writers and other literary professionals around the world are imprisoned, prosecuted, persecuted, attacked, threatened, forced into exile or even murdered as a result of their work. A significant proportion of these writers are believed to have been detained or otherwise persecuted in relation to their poetry.

Throughout this year’s Ledbury Poetry Festival (1-10 July), poets including Fleur Adcock, John Greening, Sarah Howe, Andrew McMillan, Daljit Nagra, Ruth Padel and Ruby Robinson will be taking part in ‘Poetry as Protest’, a joint initiative to highlight the many poets currently at risk around the world. Each of the poets will read a short poem or extract by the writer with whom they have been paired: through these pairings we seek to build solidarity for poets at risk around the world, and to give a voice to those whom others have sought to silence.

The poets at risk whose work will be read are Amanuel Asrat (Eritrea), Liu Xia (China), Mahvash Sabet (Iran), Ashraf Fayadh (Saudi Arabia) and Omar Hazek (Egypt).

Jo Glanville, Director of English PEN, said:

It was incredibly powerful to hear works by our detained colleagues brought to life by fellow poets at last year’s Ledbury Poetry Festival. We are therefore delighted that more than 25 poets appearing at this year’s festival will be joining us to show support for poets at risk around the world and to introduce their writing to a new audience.

Chloe Garner, Artistic Director of Ledbury Poetry Festival, said:

That poets are imprisoned and worse because of what they write shows us how potent words are, that those who use them are held in terror by such powerful governments. Ledbury Poetry Festival is proud to support the excellent work English PEN is doing.

We’re hugely grateful to all the poets taking part in ‘Poetry as Protest’ this year and for sharing their thoughts on the importance of such initiatives:

The world is so much smaller than we imagine it to be, and we can’t ignore the plight of those suffering for simply using their voice or their pen – to write or tell stories is the very bedrock of a civilisation; civilisation itself cannot be imprisoned, we must keep saying their names aloud.

Andrew McMillan

To think that a political regime can press the ‘mute’ button and consign some of us to voicelessness is a chilling comment on the world we live in. Remembering Liu Xia and making sure she gets heard is a way of asserting that inconvenient voices cannot be wished away. Reading her poetry is a way of saying we will not be bullied, we will not be silenced, and we will stake our claim to live in freedom in a world that is our collective inheritance. It’s a way of saying, Liu Xia, sister poet, you are not forgotten.

Arundhathi Subramaniam

I feel humbled and privileged to be reading a poem by Amanuel Asrat at Tongue Fu as part of Poetry as Protest at Ledbury Poetry Festival. To share my writing is a freedom I enjoy and take for granted. To read someone else’s work out loud, who has had that freedom taken from them feels both simple and terribly important. We can be voices for each other.

Chris Redmond

Hearing of our fellow poet’s tragedy is a wake up call for us as privileged poets in the West to see beyond our own work and appreciate the terror that the work of our peers can cause.

Daljit Nagra

I’ve seen a brief online video of Liu Xia reading two of her poems, secretly filmed by American PEN. I found it very moving to hear her voice and see her speaking… One of the most painfully affecting aspects of it is her inability to communicate; according to the last information I’ve seen, she’s not even permitted to read letters from her husband or he to read hers. So all we can do is try to speak for her.

Fleur Adcock

I’ve been having a conversation while tending my herbs. The conversation is with Liu Xia, with whom I’ve been partnered by English PEN. I speak with her as I carry out to the garden outside the back door bowls of water saved from going down the kitchen drain, something my mother taught me in Cape Town. Though I now live where there’s plenty of rain, it seems everywhere is Cape Town, so the water from rinsing oranges and rice runs into large and small bowls. Look, I say, the chives have sent out purple flowers, and the mint in the pot has come back after all. Water darkens the soil next to them, around them. Moss and lavender are fanning out despite the winter’s drought, the rhododendron flowers are shrinking into the buds of next year’s flowers, and the chillies and tomatoes have green shoots so like each other. I laugh because I’m only seeing metaphors, my friend, but the small stones under our knees say that the world is not here to tell us things.

Gabeba Baderoon

It is very humbling indeed to be representing the imprisoned Iranian poet, Mahvash Sabet at Ledbury. She, like so many prisoners in Iran, was arrested and imprisoned simply because of her religious belief – she is a follower of the Baha’i faith. Sabet writes in one of her Prison Poems, a collection written on scraps of paper which were smuggled out of prison:

‘I write if only to stir faint memories of flight in these wing-bound birds, to open the cage of the heart for a moment trapped without words.’

As a writer myself, I have written a good deal about war (through my poetry as well as my plays), most recently in two radio dramas, commissioned by the BBC, about asylum seekers and refugees living in Scotland. My extensive research included interviewing Iranian and Syrian refugees – one who fled from her country due to religious persecution, undergoing an horrific journey in five lorries over 40 days, another who has lost 17 close members of his family, all killed in conflict. We frequently had to stop the interviews, and resume at a later date, so hard was it for the subjects to tell their stories, much as they desperately wanted to. As writers, I believe we must be alert to the world around us. I believe that we bear a responsibility to hear and, if possible, reflect in some way, the stories of our fellow human beings. We must embrace our shared humanity.

Gerda Stevenson

I sit on a fast train as I write this, the green fields of England speeding by. Earlier this week I flew back from Berlin. Soon I will be in Ledbury for the Poetry Festival. I think of this freedom of movement, the freedoms we so often take for granted – to buy a ticket to travel to festivals of music, literature, art, to write and perform my own poetry, and to read and discuss the work of others. The freedom to joke, rage and despair on social media about politics and life, to hold strong views and speak them loudly and without fear.

I feel a deep sadness and anger that people like Iranian teacher and poet Mahvash Sabet can so easily have those freedoms snatched from them by oppressive regimes. Mahvash Sabet is in jail in Iran simply for believing what a government does not want her to believe. She is of the Baha’i faith and, along with other Baha’i leaders in Iran, she has been imprisoned for it.

A teacher and school principal, promoting learning and literacy, Mahvash was first blocked from education and then locked away under harsh circumstances. She remains incarcerated for exercising her human right to expression. She has found ways of documenting and protesting through poetry which she began to write in prison. I am moved and honoured to be reading her work at the Ledbury Poetry Festival. I, like her, believe in the power of words, and that poetry can help open ‘the cage of the heart’.

When my family lived in Mthatha (then called Umtata) in South Africa, we had a Baha’i neighbour, a gentle man who had fled persecution in Iran. I recall interesting suppers when he came over, and long discussions with my father who was a science teacher, but also an Anglican minister, a man of deep kindness and conviction. Simple freedoms, sharing food and the views of different faiths. I hope for such freedom for Mahvash Sabet, and that she, like her words, will travel far beyond the walls of brutal ideology and imprisonment. I hope in some small way that we more fortunate fellow poets can help each other in making our brothers and sisters free.

Isobel Dixon

It is an honour to be representing at Ledbury the Egyptian poet Omar Hazek, who recently emerged from a traumatic period in prison and is now forbidden to travel. My own first collections were inspired by two years spent in Upper Egypt and I am pleased to continue the connection with this troubled country by making British poetry lovers aware of Hazek’s powerful work.

John Greening

I have written one of Mahvash Sabet’s prison poems on a china plate, which I will display and read from during my 20 minute slot at Ledbury. China is given as a traditional gift for a 20-year anniversary, and is a symbol of many things including sustenance, class and smashing in celebration. Mahvash’s poem plate will symbolise celebration for Ledbury’s 20th anniversary, the courage of Mahvash’s spirit, and the fragility of humanity.

Joolz Sparkes

I’m reading some words by Ashraf Fayadh at the festival. Ashraf Fayadh has drawn attention to the excesses of the religious authorities in Saudi Arabia, and has been sentenced to 800 lashes and 8 years in gaol. He is also under a demand to publically renounce his poetry. His work looks for moments of beauty and freedom in the everyday. It needs to be heard.

Matt Kirkham

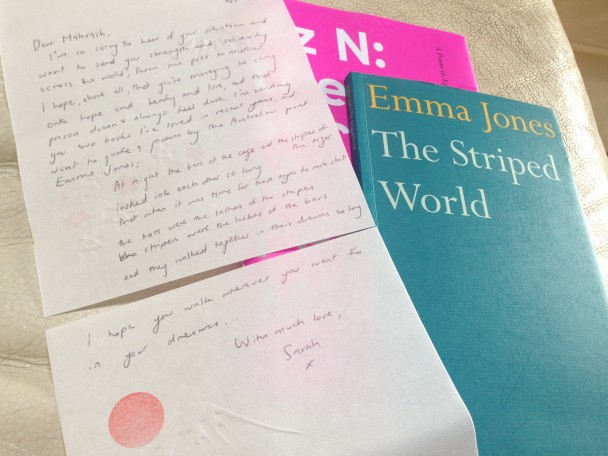

I’m honoured to have been asked to read Mahvash Sabet’s ‘Hello Again’ at this year’s Ledbury Poetry Festival. Ahead of this, I’ve sent Mahvash a copy of the poems I’ll be reading alongside her work, as well as details of times and time differences. I’m hoping it’s possible that on Saturday 9 July at midday, we’ll be connecting with late afternoon in Evin prison, Tehran.

Sarah Roby

In these times of turbulence across Europe it is important to remember how fortunate we are to live in democratic societies and to be able to speak without fear of persecution or imprisonment. The Poetry as Protest initiative drives this home.

It is vital that people are aware of the plight of those who cannot speak or who are imprisoned for speaking out against the authorities. Until I took part in this initiative I am ashamed to say I was unaware of poets living out 20-year jail terms in Iran, without legal recourse or right to appeal.

The chance to share a poem from Mahvash Sabet with an audience at Ledbury is therefore a huge privilege. The poem is a direct connection from her prison cell to the listener in Britain and as such it is a vital link that runs both ways

Sarah Westcott

I know the value of freedom, the importance of having a voice.

It is crucial to hold in our hearts and minds the voices of those whom are being hurt, incarcerated or otherwise oppressed as a result of their words, their expression.

I feel honoured to be paired with the poet Liu Xia at Ledbury Poetry Festival and given the opportunity to share her voice and her story.

I am grateful to English PEN for their crucial work to defend and promote freedom of expression and highlight cases such as that of Liu Xia.

Ruby Robinson

The English PEN and Ledbury ‘Poetry as Protest’ initiative – to show solidarity with writers at risk and raise public awareness of persecuted poets around the world – is vital. If poets don’t speak out forother poets who speak truth to power, who will? I am honoured to read at Ledbury a poem by Liu Xia, a founding member of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre. She has been under extra-legal house arrest since her husband, imprisoned poet Liu Xiaobo, won the Nobel Peace Prize in October 2010. As she says in one of her poems, ‘Gunfire of twenty years ago decided your life…/ You are in a closed room while your voice breaks out.. /You are… accompanying the souls of the dead,/ You have made a promise to seek the truth with them.’ We should all support her in that promise to seek the truth.

Ruth Padel

Here in the west, poetry is often represented as a luxury, something above the harsh realities of life, something airy-fairy and fragile. We are lucky enough to regard the arts as luxuries, but in places where life is harsher than we ever have to experience, poetry is something people need, live for, suffer for and die for. It’s poets that dictators and repressive regimes go out of their way to crush, silence and stop. So it’s an honour to stand for Liu Xia at Ledbury, and by extension for her imprisoned poet husband. She is under house arrest and separated from not only him but all her supporters and anything like a normal life. I hope she knows we are speaking and reading her words, that they are reaching people over thousands of miles.

Valerie Laws