To mark this anniversary and in solidarity with Mohammed al-‘Ajami, a prisoner of conscience held solely for peacefully exercising his right to freedom of expression, international poets will come together for a co-sponsored poetry event, Poetry under Attack, in London on 27 February 2015.

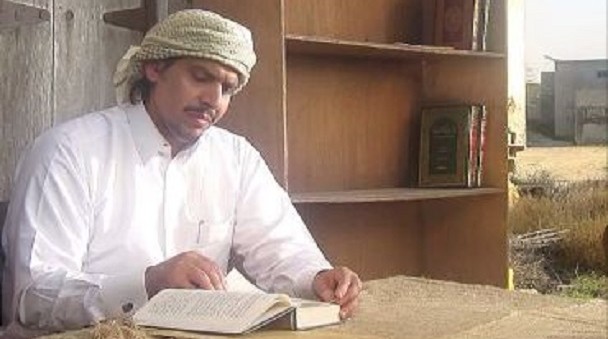

Mohammed Rashid Hassan Nasser al-‘Ajami (also known as Mohammed Ibn al-Dheeb) is serving a 15-year sentence in the Central Prison, south-west of the capital of Qatar, Doha, for writing and reciting a poem considered critical of the ruling family.

Mohammed al-‚ÄòAjami was in Egypt, studying Arabic Literature at Cairo University, when on 24 August 2010 he recited a poem (‘The Cairo Poem’) in his apartment to a group of about seven people. Unknown to him, the recital was recorded and uploaded to YouTube and it was circulated widely online.

More than a year later, on 16 November 2011, Mohammed al-‚ÄòAjami was arrested in Qatar by State Security agents in connection with ‘The Cairo Poem’. On 26 March 2012, the Criminal Court in Doha tried him on charges of ‘publicly inciting to overthrow the ruling system’, ‘publicly challenging the authority of the Emir’ and ‘publicly slandering the person of the Crown Prince’.

While the prosecution brought charges over ‘The Cairo Poem’, many activists in the Gulf region believe that Mohammed al-‚ÄòAjami‚Äôs 2011 work, ‘The Jasmine Poem’, was the real reason for his arrest. Written during the uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa that began in Tunisia in December 2010, ‘The Jasmine Poem’ criticized Gulf states and included the line ‘We are all Tunisia in the face of the repressive elite’. Neither poem called for violence of any kind.

Mohammed al-‘Ajami was sentenced to life imprisonment on 29 November 2012 after an unfair trial marred with irregularities*. On 25 February 2013, the Appeal Court in Doha reduced his sentence to 15 years’ imprisonment, and the Court of Cassation upheld the verdict on 20 October the same year.

During his appeal hearing the Public Prosecution‚Äôs examination committee interpreted ‘The Cairo Poem’ as being insulting to the then Emir of Qatar, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, even though it referred to the Emir as ‘a good man’ and expressed ‘thanks’ to him.

English PEN and Amnesty International consider Mohammed al-‘Ajami to be a prisoner of conscience, held solely for peacefully exercising his right to freedom of expression. We call for his immediate and unconditional release and for his conviction and sentence to be quashed.

Please join us by adding your name to our petition.

Poetry under Attack will be held on Friday 27 February and is co-sponsored by Amnesty International, English PEN, Poet in the City and Farrago. Amongst the performers and contributors will be Alsaddiq Alraddi, Imtiaz Dharker, John Paul O’Neill, Karim Abid, Molly Rivkin, Sabrina Mahfouz and Sophia Walker. The event is free but please make sure to reserve your place online. The event will also be live-streamed via a webcast on Amnesty International’s website (further details here.)

* Unfair trial concerns

Mohammed al-‚ÄòAjami’s investigation and trial were marred by irregularities. Al-‚ÄòAjami was held incommunicado for three months before he was allowed visits from his family. He was not told of the official charges against him, even after the six-month period during which, under Qatari law, detainees can be held without charge for investigation. During interrogation, Mohammed al-‚ÄòAjami was made to sign a document which stated, falsely, ‚Äúthe poem was read in a public place in the presence of the press’.

The trial before the Doha Criminal Court was held in secret and his lawyer was prevented from attending two court sessions because he objected to such secrecy. Mohammed al-‚ÄòAjami himself was not told the date that the final hearing would take place, and so was not present in court on the day the verdict was issued, even though the judge pronounced in court ‘on the attendance of Mohammed al-‚ÄòAjami, we have sentenced him to life’. Despite petitions to the judge about Mohammed al-‚ÄòAjami‚Äôs treatment, throughout the pre-trial investigations he was held in solitary confinement in a very small cell, in which he could not lie down without pressing against the lavatory. He has spent most of his detention in such conditions.

Background

Freedom of expression is strictly controlled in Qatar and the press often exercises self-censorship. The right to freedom of expression is further threatened by the 2004 Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Convention for the Suppression of Terrorism, the provisions of which risk criminalizing legitimate activities. The Qatari government acceded to this convention in May 2008.

In November 2012 Qatar signed the GCC Security Agreement. This agreement contains provisions  for the suppression of legitimate and peaceful expression such as criticism of state action in the region and possibly elsewhere, and for the forced removal from a given country’s territory of those who have been charged or convicted in another state party.

Since 2011, State Security (which runs its own detention facilities) has detained a number of people simply for exercising their rights to freedom of expression and assembly. Many have reported being tortured or otherwise ill-treated before they were charged or put on trial, particularly during periods of incommunicado detention. Activists in Qatar have raised concerns that State Security personnel, generally operating in plain clothes, do not identify themselves when carrying out arrests and have been holding detainees in police detention centres rather than State Security-run facilities. Their aim appears to be to deny responsibility for carrying out particular arrests and detentions and thereby to deflect criticism about their working practices.

On 8 January 2013, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights expressed its concerns over the fairness of Mohammed al-‘Ajami’s trial, including the right to counsel. In January 2014, the UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Gabriela Knaul, undertook a research mission to Qatar. She thanked the Qatari government for its co-operation but identified a wide range of flaws with respect to the administration of justice. Gabriela Knaul will present a report on her visit to the Human Rights Council in Geneva in June 2015.

Qatar‚Äôs human rights record was reviewed in May 2014, in the non-binding and state-led Universal Periodic Review process held at the UN Human Rights Council during its 19th session. The government stated that ‘Qatar believed in freedom of expression in the media and on social networks, except in the case of violations of moral principles and sharia law’ and asserted that ‘All measures taken against the poet Mohammed al-‚ÄòAjami were consistent with international rules. Mr. al-‚ÄòAjami had been given a fair trial and allowed to appeal the judgement to the Court of Appeal and the Court of Cassation.’ Amnesty International and English PEN believe that this statement misrepresents the facts of the case.

Mohammed al-‘Ajami has published many poems, some of them in praise of Gulf leaders, and others critical of other poets or the authorities. These poems have been elaborated in the traditional forms of praise (madah) and satire (hija’), two well-known genres of Arabic poetry. In each genre, the poet’s sole objective is to deliver praise or criticism with the most imagination and best poetic arrangements in order to take the rival poet out of the contest. These two genres of poetry, unlike other genres, have always had a political aspect and have been a form of freedom of expression used by people and political leaders to criticize their opponents and praise their allies.