Paul Ewen was among the writers invited to perform at the English PEN Modern Literature Festival V at this year’s Greenwich Book Festival. Six UK-based writers were paired with writers at risk supported by PEN and asked to create and perform new pieces of work in response and in solidarity. This is Paul’s piece for Behrouz Boochani.

Behrouz Boochani is an Iranian-Kurdish journalist, writer, human rights defender, poet and film-maker. He has been illegally detained by the Australian government on Manus Island for over six years, after being forced to flee Iran and undertake a life-threatening boat journey, along with other asylum seekers. Behrouz has written: ‘We are a bunch of ordinary humans locked up simply for seeking refuge. Exiled. Imprisoned without charge.’ His book, No Friend But The Mountains, details the extreme oppression and hardships in the Manus Island Detention Centre, as a result of the Australian government’s inhumane refugee policy.

With the recent Australian election, the situation in the Manus Detention Centre has become even worse. The prospect of a new Labour government offered hope of an end to the refugees’ plight. Instead, the re-election of the Scott Morrison-led Coalition Government has extinguished that hope. As Behrouz himself reported in the Guardian, just over a week ago, in the short time since the election, at least 26 refugees have attempted suicide or severely self-harmed. He added: ‘In order to move beyond this critical situation only one option exists: that is for the Australian government to abide by the international laws which it is obligated to; it must acknowledge the human rights of refugees. There is no other way to act on this but to free the innocent human beings who they have tortured systematically for years.’

While detained on Manus Island, Behrouz wrote No Friend But The Mountains via a series of single text messages on a smuggled phone. The book won the prestigious Victorian premier’s literary prize.

In the book, Behrouz returns often to his memory of the chestnut oak tree. In his Kurdish homeland, the people found asylum within chestnut oak tree forests, while a devastating war was being waged upon them. In the searing heat on Manus Island, there aren’t any chestnut oak trees, but Behrouz does write of mango trees, which surround the detention centre.

Today I’m going to read a short piece written for Behrouz, based on the chestnut oak tree and the hope of refuge, which it carries. The piece is called ‘Swap’.

Swap

It was just after four in the morning when I broke into Kew Gardens. It was my only option. The grounds were all fenced off, with high gates and uniformed security guards. Trees, it seems, are very precious things.

Inside, using a map of the surrounds, I cautiously crept off the lighted paths, attempting to avoid the sound of kicked leaves underfoot. Near an outbuilding, I found my first object of interest: a mango tree. With my torchlight, I revealed more leaves, mango leaves, gathered on the ground beneath it. Working quickly, I began picking these up, every last one, including the sticks and the twigs. Collecting them in a thick sturdy bag, I silently set off in search of my second location.

The English oak, also known as the common oak, is the most common tree species in the UK. But the chestnut oak is a much rarer thing. In Kew Gardens there is a particularly fine specimen, which was first introduced to Kew in 1843. Today it stands at over 36 metres, and has been crowned the ‘National Champion Chestnut Oak of the UK’. Its green leaves, unlike the longer, rounded edges of the mango leaf, are indented, almost perforated, in appearance. My torchlight soon picked out many of these, dispatched onto a wide catchment of grass, from this giant of trees. Making a careful note of their arrangement, I began gathering them into a pile, which I placed just outside of the drop zone. In their place, I began loosely dropping mango leaves from the mango tree. When the bag was empty, I refilled it with the leaves of the chestnut oak, before retracing my steps, back to the mango tree.

Attempting to closely replicate their natural, scattered arrangement from before, I began redistributing the chestnut oak tree leaves on the grass and roots beneath the branches of the mango tree. I took particular care and attention with this task, and after a few final leaves and twigs had been painstakingly shifted, upended and turned, I sat down, leaning back on the trunk. From here, surrounded by fallen chestnut oak leaves, now lit by the first rays of escaping sun, I imagined I was not beneath a mango tree, in a fenced-off area patrolled by security guards, but in a safe, welcoming place where one could feel free.

PAUL EWEN is a New Zealand writer based in south London. His work has appeared in the British Council’s New Writing anthology, the Guardian, the TES, and Five Dials. Paul’s first novel, Francis Plug: How To Be A Public Author, was published by Galley Beggar Press in 2014. It went on to appear on numerous Books Of The Year lists, won a Society of Authors McKitterick Prize, and was described by the Sunday Times as ‘a brilliant, deranged new comic creation… the funniest book I’ve read in years.’ Paul’s latest book, Francis Plug: Writer in Residence, was shortlisted for the 2019 Bollinger Wodehouse Prize for Comic Fiction.

TAKE ACTION

To mark World Refugee Day, PEN centres around the world are coming together to stand in solidarity with Behrouz Boochani. Find out more and take action.

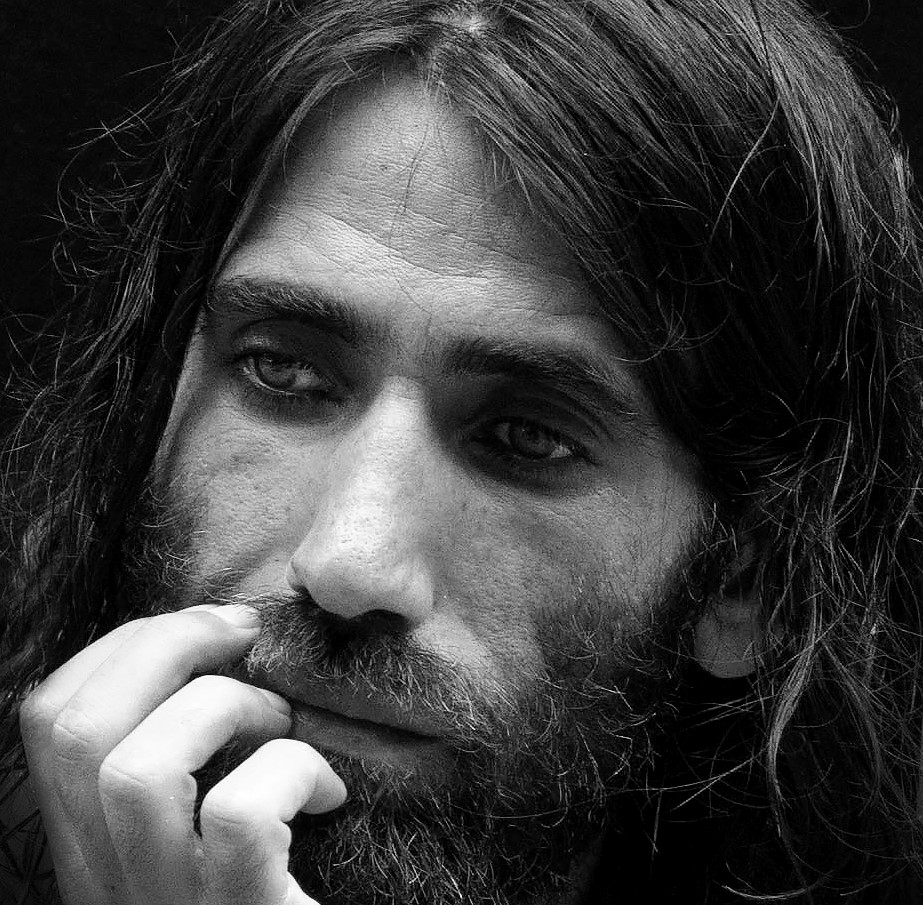

Image credit: Hoda Afshar, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Video credit: SJ Fowler