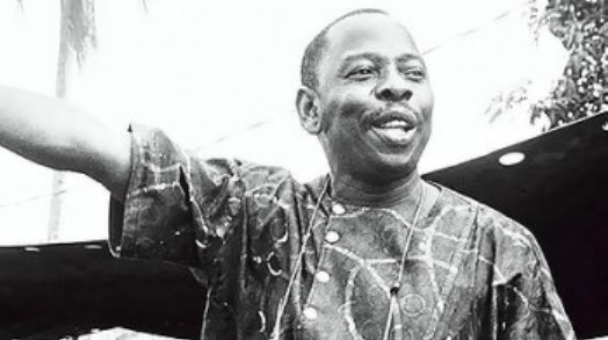

Ken Saro-Wiwa, one of Nigeria’s most beloved writers, was executed in Nigeria on 10 November 1995. He was arrested the previous year and charged with incitement to murder. The underlying reason for his arrest and conviction was his outspoken opposition to Nigeria’s successive military governments and his defence of the Ogoni tribe, of which he was a member. The Ogonis live on land that has been environmentally degraded by intensive oil extraction by multinational companies.

Twenty years on the campaign for justice continues. As his son, Ken Wiwa, writes in today’s Guardian:

Despite several aborted attempts to reconcile the victims and perpetrators, my father and the other men remain convicted criminals in Nigeria’s legal books. More worrying is that, although the military junta that killed my father is long gone, Nigeria’s civilian government has yet to come to terms with a man and a community whose story stands as enduring testimony to the consequences of reckless and unaccountable oil production.

Last week it was announced the Nigerian government had impounded ‘The Bus’, a sculpture created by Sokari Douglas Camp in memory of Ken Saro-Wiwa and his fellow activists is, reportedly on the grounds of its ‘political value’. PEN condemned the seizure with Salil Tripathi, Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee, stating:

Twenty years ago a Nigerian government executed Ken Saro Wiwa and eight Ogoni leaders in a trial that failed to meet international standards. Today, another Nigerian government has impounded a sculpture commemorating him, attempting to stifle his voice once again. His voice lives, resounding across not only the Niger Delta but throughout the world. Nigeria should undo its past and not repeat history; its government must not only return the sculpture but enter into a meaningful dialogue with the Nigerian people so that healing can begin.

These continued attempts to silence Ken Saro-Wiwa and his supporters only make us more determined to support his family in their calls for justice, and to ensure that his voice continues to be heard far and wide. To mark the 20th anniversary of his death, we are therefore honoured to publish this extract of Ken Saro-Wiwa’s writing, written in prison just days before his execution and smuggled out to PEN*.

On the death of Ken Saro-Wiwa

Physical torture did not kill me. Nor did mental torture. Then, one night, the ghost arrived. Tall and gangly, dressed in ragged Nigerian Army camouflage uniform, his bones shooting out of holes in his uniform, his brown teeth as huge as tusks projecting from enormous lips, he came to me, automatic weapon slung over his shoulder, a little drum, an Ogoni drum called ‘Ekoni’ in his hand. He sounded the drum, Ken-ti-mo, Ken-ti-mo, Ken-ti-mo!

The familiar sound of the little drum woke me up. At the sight of the ghost, I laughed. Annoyed by my laughter, he dropped the drum and laid hold of his automatic weapon. He pointed it at me at close range. I did not flinch. He cocked the weapon and fingered the trigger. I did not bat an eyelid.

‘Who are you?’ I asked.

‘I’m General Jeno Saidu’.

‘Sounds like genocide to me’ I said.

‘You should know’.

‘What do you want?’ I asked.

‘I’m here to finish you’ replied he, in a gruff voice.

‘General, stop swaggering. You do not impress me’.

‘You will be impressed. I’ve finished all your Ogoni people—men, women and children. Once I deal with you, my task is done’.

‘Go ahead’ I challenged him.

‘You are not afraid to die?’

‘No’

‘Why not?’

‘I’m prepared to go with all my people whom you confess to having already murdered’

‘Yes, I worked hard on them. I made short work of them. All five hundred thousand of them. You are the last man’.

‘So go ahead’

General Jeno Saidu the ghost, shot into the ceiling. I laughed.

‘Why did you shoot into the ceiling and not into my chest?’

‘You’re still not afraid?’

‘No General.’

‘And why not?’

‘Because I have what is greater than your weapon.’ Whereupon, I said after the English poet Blake:

I will not cease my mental fight

Nor shall my pen sleep in my hand

Till we have built a new Ogoni

In Niger delta’s wealthy land.

Then I drew my pen from under my pillow. The General’s weapon fell from his hand, and he slumped to his knee…

****

When the news came that Ken Saro-Wiwa had given up the ghost in the offices of the State Investigation and Intelligence Bureau in Port Harcourt, there was a flurry in newspaper houses in Lagos as in many other places in Nigeria and abroad. I was hurriedly dispatched to cover the story.

I found, on arrival in Port Harcourt, that the funny little man had given up the ghost a few days after this interrogation by men of the Federal Investigation and Intelligence Bureau from Lagos, leaving behind an epitaph to be put on his gravestone, and a hurriedly written note explaining why he had decided to give up the ghost.

His presence in the office of the State Investigation and Intelligence Bureau is explained by the fact that he was refused accommodation in the dingy, damp, smelly guardroom where men in police custody were normally kept. Senior police officers who knew their onions and had information of the plot against the man decided that they would not have his blood on their hands. Eventually they found him a place in an office where he bathed, ate and slept – for three nights running and was able to write his story as advised by the ghost.

There was great jubilation at Government House, Port Harcourt, the headquarters of the notorious Rivers State Internal Security Task Force. Champagne bottles popped endlessly. Military buffoons gleamed. Boots shone. The Commander of the Task Force shook hands with the Military Administrator. The former knew that he would soon be promoted to the rank of General. The latter knew that his position was secure and he would soon be nominated to Nigeria’s highest-ranking body, the Provisional Ruling Council. The Task Force had successfully completed the genocide of the Ogoni people.

All that was left was to dispose of Mr. Saro-Wiwa’s corpse. There was a debate as to how best to carry out this Task. In the first place, there were none of his relatives alive, all Ogoni people, men, women and children having fallen to the gallant troops led by the deadly ghost, General Jeno Saidu. The telephone to his house and office had been cut to deprive his family of sustenance and ruin his business. His poor family had fled to London before they would be murdered. This knotty problem was solved when it was decided that it was a Task and therefore the Internal Security Task Force should be assigned the responsibility.

Next was where he should be buried. This question was quickly settled. The entire Ogoni territory had become a cemetery. The hundred thousand Ogoni people had all been buried. Ken Saro-Wiwa would cap the mass burial ceremony.

So, as is usual in Nigeria, a contract was awarded for the burial of the little man. The officer who won the contract for supplying the coffin, to maximise his profit for the deal, decided to hire a carpenter to make it. He gave the coffin-maker precise instructions. The coffin had to be no more than five feet long and one foot wide. The shocked carpenter succeeded in making the coffin to specification. But, being a Nigerian, and therefore innumerate, he actually made it two inches shorter either way. This also saved money.

Poor Ken was squashed into this contraption. And being used to protesting injustice, his corpse squeaked and screamed. The officer who had won the contract for putting Ken in the coffin ran for his dear life. So the Military Administrator had to do the job himself. He duly cancelled this aspect of the contract and demoted the officer for cowardice.

Then the soldiers who were to act as Pall bearers refused to do the job on the allegation that they had not been paid their Ration Cash Allowance (RCA) for exterminating the Ogoni people. The Commander of the Task Force paid the money on the spot, and the bier was borne through Port Harcourt to show all the residents and other Nigerians what it costs to demand an end to environmental degradation and pollution by oil companies and social justice for the poor and oppressed.

When the funeral procession got to Ogoni territory, it was no surprise to find Shell, Saipem, Ferrostaal, Chevron, and a gaggle of industrial oil contractors from Europe and America. This helped to give the burial of the little man a well-deserved international flavour since he had made it a point to complain to the international community about the dehumanisation and denigration of the Ogoni people and other peoples of the Niger delta.

Shell and Chevron who have oil-mining leases covering the whole of Ogoni territory chose the exact spot where the funny little man was to be buried. Care had to be taken, they said, because all the Ogoni land was a huge oil well and now that human beings, flora, fauna and all had been disposed of, oil exploitation could go on without it or hindrance or protests about ecological war, double standards, hypocrisy, acid rain, gas flaring and all.

The right size of hole was dug – tiny and narrow, no more than five foot by one. And the coffin was lowered, and wait for it, stood upright – to save space. Which fulfilled Ken’s prophecy in his epitaph which was duly laid on the grave:

Here stands the funny little sweet

The Nigerians loved to cheat

So much so that e’en in death

They denied him six feet of earth.

As the procession made to go, a message flashed across the sky like lightning: “Congratulations, congratulations to the Internal Security Task Force. Your success has won for Nigeria unanimous election to Permanent Membership of the United Nations Security Council.”

And Ken Saro-Wiwa laughed in his grave.

*This extract first appeared in English PEN’s anthology Another Sky: Voices of Conscience from around the world, edited by Lucy Popescu and Carole Seymour-Jones.