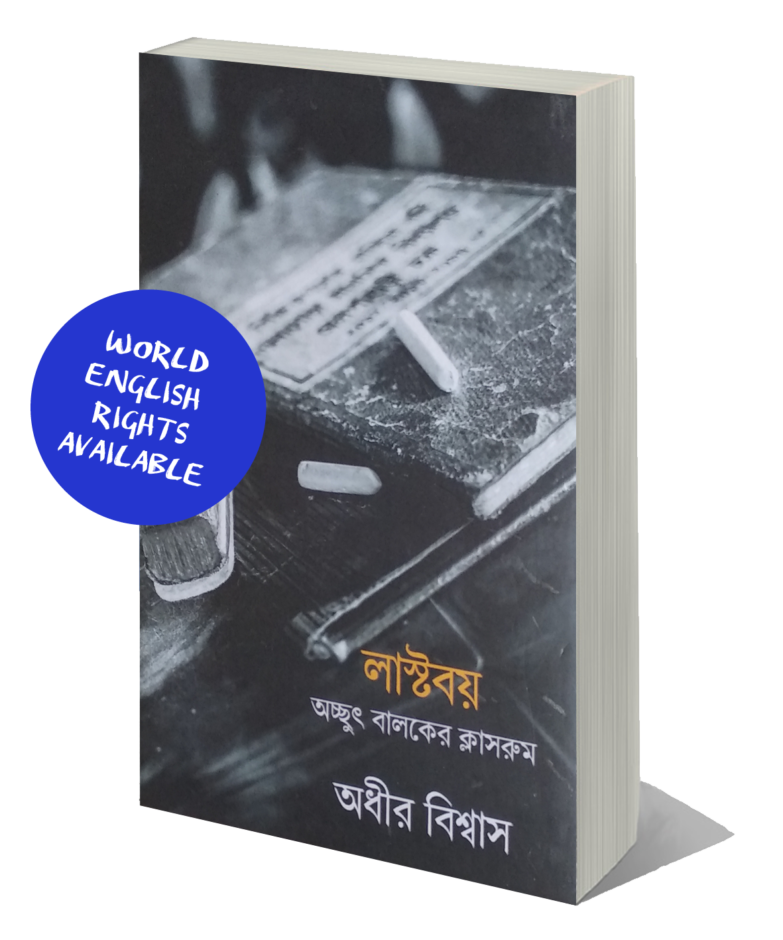

About the book

In Last Boy: An Untouchable Boy’s Classroom, the author remembers his childhood in a village by a river in East Pakistan, and his years at primary school there. He was the youngest of the four surviving sons of a poor barber and his sick wife. In this book, his mother is alive; it was shortly after her death that they left their country in 1967. Even before he joined school, his bedridden mother had urged him to help his father, and so he hailed customers to his father’s barber shop on the market days. One day, he draws a customer by calling out to him politely. It turns out to be a teacher at the local primary school. While his father gives him a haircut, he requests him to admit his son in school. The boy is eager to go to school and yet loath to leave his sick mother behind. However, once he enters the new world of the classroom, he is very soon made to sit at the back because of the foul smell from the pus oozing out of a boil in his ear, and from his clothes.

Thus begins the tale Adhir Biswas narrates in this trilogy. The cryptic flashes of memory lend a different literary character to what could be called a poetic testimony. The alienated Dalit childhood of Adhir comes up in translation, imbibing the original childlike simplicity of narration and yet communicating the pain and abjection experienced by a Dalit child in a casteist society. The author is a keeper of memories. They are very personal, but they also tell us about a time, place, and the social milieu in the early years of a quirky, feisty survivor, who later embraces an unremitting aspiration to be a writer.

Why the Selection Panel chose it

Ramaswamy’s meticulous, visceral translation of Adhir Biswas’ memoir realises the compelling voice and aesthetic of the original Bangla, conveying the simultaneous hope and trauma of this story. Part of an important trilogy examining casteism and a gamut of related themes, this book should be available to readers across the world.

Awards and press

“A movingly told life story.” – Ei Somoy

Rights available

World English

Translation extract

Childhood Repulsion

Your father touches you, as do your forefathers. They touch you with their caste. ‘Whose son are you?’ ‘To which caste do you belong?’ ‘But you people are Paramanik. Aren’t you barber folk?’ It began right from my school days. Back in primary school. ‘No, not here. Your place is at the back, on the bench at the back.’ Why? Someone might provide an answer, but they might just as well not, because you had to know the answer in your own head. You belong to a low caste. You are not supposed to talk loudly. You should not stand with your head raised high. The front bench is not for you.

Baba used to say, ‘Study, keep studying, Ratan. If you do well in your exams, I’ll give you something.’ Baba is no longer alive. I too am approaching the end of my days. My lost childhood beckons me. The day of my hatekhori, my school life, my classroom, my last bench. My friends from my school days – who have moved very, very far away from my life – and my teachers as well, they all keep waving to me even as they fade away. My Baba. ‘If you study well, I’ll give you something.’ I never, ever did well in studies. But life endowed me with a lot. The school life of my childhood, the casteist slurs – all the memories crawl out together. They look at me and laugh. With eyes full of mischief, they keep telling me something. As if they keep asking – didn’t that childhood repulsion give you any strength at all? Did you get nothing at all from it?

*

I was so happy

Baba had opened the shop a long time back. No customers had come yet. It was to fetch customers that I was hovering around in front of the Kali temple. If I spotted anyone, I would call out and bring them along. People with long hair and unshaven faces.

Fetching people was my job. If I did it well, Baba would definitely give me an anna. It wasn’t noon yet, but did that mean that the day’s first custom couldn’t happen? Seeing me standing quietly, Baba called out. ‘Will you go to Kobrej Moshai? If you go to him and mention my name, he’ll recognise you. He’ll give you a bottle of herbal decoction. Tell him Baba will come and give the money after the market closes.’

I said, ‘I’ll go,’ and continued looking for customers.

But Kobrej Moshai knew me too! Whenever I went to him, he would ask, ‘How’s your Ma?’

‘The same,’ I would reply. ‘But she was very breathless yesterday.’ Or, ‘She’s just been sleeping for the last two days, I didn’t see her open her eyes. She’ll get well, won’t she, Jaetha?’

No, I couldn’t really spot any customers. I had to spot people walking my way from three directions. As soon as someone neared, I hailed him. ‘O Chacha, will you have a haircut? A shave?’ They walked away without saying anything.

I only stood there on the days of the haat. The rest of the time, it was people from nearby villages who came. Most were known folk who had haircuts on credit. One had to cut their hair even if they didn’t pay. If you didn’t, they would go to another shop. It was better to give haircuts on credit than to be sitting idle. But there weren’t too many barber shops. Only three that we knew. Debu-da, Shyama’s Baba, and ours.

We all lived in the same village. Because we were all in the same trade, there was a little bit of rancour. Rancour didn’t mean any quarrel. It was about getting more or less custom. Debu-da’s shop was just beside ours. If customers went there instead, I would get angry. But Baba thought differently. He gazed at that shop, then turned his eyes away. He only said, ‘Debu’s lucky today!’ I would realise then how harsh it felt when the first customer failed to materialise. The others in the trade sat on bricks, near the rice mill. They wet the beard or stubble with water and ran their razor. They charged half what we charged in the shop.

This marketplace in Magura was called ‘New Market’, and the old one was called ‘the other market’. This haat ran twice a week, on Sunday and Thursday. Ma would push me to go. ‘Go quickly, he’s all alone, how’ll he hail customers when he’s working? Go, my precious boy!’ I suddenly spotted a man of Baba’s age. He had a bag in one hand, and a basket in the other. For vegetables, for fish. Bottle-shaped baskets like that were for fish. They had red bands around their necks. Yes, it looked like he was coming this way! After all, his hair did seem long.

People had passed by earlier – was that because I wasn’t calling out to them properly? This time I asked softly and courteously, ‘Will you have a haircut, Kaku?’

He stopped as soon as he heard me. Why was he looking at me like that? He asked, ‘Will you cut my hair?’

‘Not me, my Baba. I can cut nails.’

I thought he was a good man, or else why would he ask me that? It was because he was good that, as soon as I touched his hand, to my surprise, this Uncle-man enclosed my hand in his and led me to our shop. Baba looked pleased.

‘Master-moshai!’ he exclaimed. And then he offered the stool courteously and said, ‘I was looking for you. I’m lucky, the Almighty let us meet!’

‘Who’s this, Narayan?’

‘He’s my little son.’

‘That’s what I thought, who else but your son would call me so lovingly! So, tell me, why were you looking for me?’

‘Admit my son in school, Master-moshai! After all, he must study, mustn’t he?’

‘That’s very good. Hey, what’s your name?’

I felt terribly shy. Hadn’t I just asked him about a haircut! Seeing me silent, Baba said, ‘Tell him, tell him your name!’

After I told him, it was to Baba that he directed his question. ‘Is his hatekhori over?’

‘Yes. Fatik Thakur did that last year.’

‘Then there’s no problem. Class 1, right?’

‘I guess so. He knows to say the alphabets, he knows it by rote.’

‘He’s such a big boy now and yet you folk don’t send him to school!’

‘What can I do, Master-moshai! You see we don’t know about such things!’

‘Then it’s Class 1. The admission fee is six annas. How much for the haircut did you say?’

‘Thank you. It’s four annas.’

‘So, what’s the balance then?’

‘Two annas.’

‘Give me that after you cut my hair today, he’ll be admitted.’

I was going to school! A slate. A wet rag. Books, with paper covers. I could see everything in my mind’s eye. Crossing a river before reaching the school. By a bamboo bridge. The river Nabaganga. The school shed with a thatched roof of shon-grass laid over old log rafters. Once people crossed the riverside jetty at the bridge, they had to pay two paise. But students didn’t have to pay. And as soon as you passed the pakur tree, there was the Nanduyali Free Primary School. The bell signalling the end of school. Dong, dong, dong!

Baba was taking a lot of time cutting Master-moshai’s hair. He was giving him more time, so that his hair would be cut well, because I was going to be admitted to school. I was so happy that I didn’t have the words to describe it. I didn’t want to go back to standing outside the shop again. When would I start going to school? Had Master-moshai dozed off? I’ll tell Baba to ask him when he wakes up – was it in the thatch-shed across the river that Class 1 sat?

But even before I thought about that, Baba said, ‘Go to Kobrej Moshai. Once customers start coming, you won’t be able to leave.’

The customers had to be asked to wait at the bench, the stool had to be extended to them, change had to be fetched. There was so much work, then. If someone was in a hurry as they sat on the bench, I had to say politely, ‘Don’t leave. Chacha!’

If someone had no moustache and wasn’t wearing a lungi, he must be a Hindu. I had to say, ‘Just wait a bit, Kaka! You’ll get your shave just now.’ But if the customer got up to leave even after that, Baba himself would say, ‘Wet his beard!’

I would do that at once. Apply shaving soap on the brush and slather the foam on the face of the customer sitting on the stool. And he couldn’t leave after that. He would think, not much longer now. If he stayed back, that meant two annas.

I had thought that by the time I returned with the medicine the shop would be busy, and Baba would say, ‘Go and shake out the towel. Run and fetch change, Chacha’s waiting. Go to Wahid’s shop and ask him to keep five annas and give change for the balance.’ If one had a haircut as well as a shave, it was five annas instead of six. A discount of an anna. But no, there was none of that. Baba was sitting idle. Why was that so? After all, the haat was crowded with people. If customers didn’t come now, when would they?

Seeing the shop empty, I had a sinking feeling inside. Hadn’t I told Kobrej Moshai that Baba would come and give the money after the haat? If the shop was empty, how would he be able to do that? Had no one come after Master-moshai? Did Baba have change to give them? Would my school admission then have to be on credit?

*

Are you barber folk?

Ma had asked me to wait a bit. But that had been a long while back! How much longer? What was she looking for inside the room? What was needed now? I couldn’t understand why she had asked me to wait. Oof, why did she have to do this when I was in such a hurry! Should I leave? No – maybe she’d give me something. Had she gone to get some money? It wouldn’t be bad if I got some. I was beginning school. It was my first day. If not an anna, even two paise was good. But I wouldn’t wait long for that! Let’s see what Ma brought.

I could easily run all the way. If Ma held me up like this, I’d just simply leave! But because it was the first day, I didn’t. She was going from one room to the other. I know that Ma couldn’t move about like us. The toll that the suffering from her sickness had taken! I saw Ma every day, but I had never observed her like I was doing now. For so long. And all the while, it seemed to me that Ma was moving around with a sari of slender skin wound around her.

She had her medicine. The decoction from the Kobiraj-moshai. Pills. A powder. Once she had those, she began cooking for the household. Baba lent Ma a hand. Cutting the vegetables, washing them, washing the utensils, preparing the dough. Sometimes Ma would say, ‘Leave it, I’ll do it.’ Sometimes Baba would say it. He wasn’t at home all the time, so he tried to do some of Ma’s work in the few moments he got. But why wasn’t Ma getting well despite all that?

‘Oh Ma, it’s getting late! What are you doing? Tell me what you’re looking for.’

‘What else! The kohl container. It was next to the candlestick. Did you move it somewhere?’

‘Aah!’ I said impatiently. ‘What do you need the kohl for?’

‘Oh dear! What are you saying? You’re beginning school, won’t I put a dot on your face?’

‘What’ll happen if you don’t put it? I’ve grown up now – I’m off!’

‘Wait.’ I had never heard Ma snap so loud! She wasn’t angry, and it didn’t seem scolding either. It was like a capricious insistence. I was annoyed, but I couldn’t move. Ma walked slowly towards me, coming closer, and before I knew it – what’s this – she held my head and kissed me on my forehead! ‘Do your studies mindfully, my dear, I’m afraid I won’t be there to see it all!’

The thought of school vanished at once from my mind. Why was she choking? As she swallowed, she snuffled a little. Her eyes were brimming with tears. As if she was going just now… I said softly, ‘Are you crying, Ma?’

‘Where? No!’ And saying so, she wiped her eyes. ‘Go now!’

What if I went after a few days instead? Or never went at all, so I could stay home with Ma? Could I not learn a trade like Baba’s rather than go to school? After all, I had gone to a house where there had been a bereavement, and their pregnant daughter was also there for her confinement. I had cut the nails of the people in the household. The womenfolk there had gently held out their hands. One finger at a time.

A clay bowl full of rice in return. The aush rice had a brown colour. Round potatoes, and sometimes clinking coins. So what if I was small? After all, I belonged to that caste! I filled the bag with fistfuls of rice. The vegetables would be placed on one side. But that came later. As soon as the bag was full, I could hear someone from the household say, ‘Don’t keep sitting there, come to the back of the house, come to the back and have lunch.’

I could see it all, as if Thakur-moshai, the priest, was sitting far away from me. A banana leaf was full of rice, dal and vegetable curry. After mixing them, and before eating, I licked up the starch on my palm and fingers. Time and again I would think, no one was watching me eating, were they? Oh, how long it had been since I had eaten so well!

In front of Thakur-moshai were Kakima and others of the household. I was served a lot of rice and vegetable curry, and it took a while to eat that. From the verandah someone called out, ‘Just ask if you want more rice.’

I wondered – wasn’t there anything else? Some fish? Maybe not the choicest piece, but perhaps a tail piece? But then I thought, where’s the need for that? With what I had been served, I wouldn’t have to eat till noon tomorrow. I continued gorging. As I ate, I began to feel drowsy.

What was wrong with that? If I went around from village to village with a nail-cutting chisel, I would be able to start earning right away. I wanted to stay close to Ma. I wouldn’t go to school! What if she kept on crying if I went to school?

Ma understood, there were tears in my eyes. She wiped them and said, ‘Go, my dear, it’s getting late.’

I didn’t say no. Once again, the urge to go to school awakened. I said, ‘So I’m going!’

Ma nodded.

I had gone quite a distance. But Ma was still standing on the road in front of the house. I turned back every now and then to look. Ma waved her hand.

My Dadas had already gone out. Ma had said to Chhor-da, ‘Drop your brother at school tomorrow.’

‘He’ll go on his own,’ he had replied. ‘Why are you worrying? He wanders around everywhere all day, won’t he be able to get there?’

Baba had left for his shop quite early in the morning. Mej-da was sleeping. Bor-da had left for Boudi’s father’s house.

As it is, my Dadas never ventured towards the shop. They were ashamed that Baba did this job. A friend of one of my Dadas teased him, calling him ‘barber’. He couldn’t really say much in reply. But I knew that if I was ever rude to my Dadas, they smacked me. And they called me by that name too, ‘Hey you son-of-a-barber, you blackie.’

My Dadas made sure to walk at a distance from where the shop was. I didn’t feel at all bad that no one was going with me to school. Why would I? After all, I went around everywhere on my own. I knew all the places! There was Ma, still standing. Once I turned at the curve of the road at the banyan tree, I wouldn’t be able to see her anymore.

A tin-roofed shanty. It had no walls, nor a fence – just posts on the four corners and a tin sheet on top. That was the school. The cement floor was chipped and broken in places. Everyone had sat down, keeping just those parts vacant. The room was almost full. I wondered where I would sit. I looked here and there. There was such a clamour! I couldn’t fathom anything. It was Class 1, wasn’t it? Was I in the correct classroom? Was anyone from my village here? I tried to identify them. Where did Sir sit? Just as I was about to enter, wondering, I heard, ‘Ratan!’ Who called me?

I entered. Who called me? The students were like a shoal of squirming fish. Who was it?

Everyone had a slate in their hands. And a wet rag. What was the book they held? The same call again, ‘Ratan!’

‘Hey Dulal!’ I said and smiled. Did I say that too loud? Everyone turned to look at me. Dulal was the son of the sister-in-law of Punyo Majhi from the riverbank. Not exactly from my village, they lived a little distance from the banyan tree. He was my marbles companion. As soon as I hovered outside his house, he knew that I had come to play, and we would make a clearing in the wooded part.

Baba had come to recognise him. If he ever spotted him outside our house, he would come running and hit me. Baba only had to say, ‘Marbles again?’ Just that. And if Chhor-da heard it, he too came running. Sometimes the thrashing left me with a bleeding nose or a split lip. It was when Chhor-da hit me that Ma got frightened. Even if she couldn’t get up, she wanted to ward it off with all her strength. She would want to hold him back. And if it was Baba, she would weep, ‘Oh dear, you hit him so badly, I’m going to lose Ratan! Hit me instead.’

Dulal would run away when he heard the thrashing and weeping. It was the same Dulal. He asked, ‘When did you get admitted?’

‘Yesterday, at the haat. When a Sir came for a haircut.’

Dulal knew that the Sir admitted students outside school as well, in the market, or at a shop. He didn’t want to know any more. He said, ‘Sit down. Sir will be here in a little while. When he calls out your name, say ‘Present sir!’

The boy beside me asked, ‘Where do you live?’

‘You know the banyan tree? If you go a bit beyond that, the house with the banana-leaf fencing. You’ll see a threshing hut slanting beside the road, with bamboo supports. That house. Isn’t Sir going to come?’

‘Oh, he’ll come. He’ll be here. Where’s your book?’

I was silent. Had Sir mentioned anything about that?

A boy wearing pants torn at the backside slid towards me and said, ‘I think I’ve seen you somewhere.’

‘Was it at the shop?’

‘What’s your shop?’

‘A barber shop.’

‘Are you barber folk?’ The boy was bare-bodied. I was looking at Sir’s chair. The broken handle was fixed with string. I also noticed a boy with a dot of sandal paste on his forehead. Was he also a new student like me? The other boy suddenly grabbed my shirt. And then he said, ‘Why aren’t you telling me?’

I was in Class 1. Back in East Pakistan, the hatekhori ceremony used to be carried out in Hindu households once a child turned five. The days had flown by since then. It had been a year or two. And now I was admitted to school. So how old was I then?

I was scared. Would he hit me here, inside the classroom? Why does everyone hit me? Was it because I was dark-skinned? Or because I went to other people’s houses to work? If Baba was not in this line of work, would they have let me join their games, would they have not hit me? Perhaps it would have been best if I hadn’t come to school today. How tearful Ma had been!

Seeing that I wasn’t saying anything, Dulal asked him, ‘Is cutting hair bad? Can you go without having your hair cut? My uncle catches fish, which he sells in the market. Is that bad work? So why do you think of caste?’

The boy was much bigger than me. ‘Come, Ratan,’ Dulal said. ‘Sit here.’

The field in front of the primary school was very green. The schoolhouse there was south facing. It was Dulal who told me ‘Once we’re in Class 2, we’ll go to that nice schoolhouse.’ The din was gradually coming to a close. He said, ‘There’s Sir.’

‘But I know him! I’ve seen him walking along the riverbank. He’s from Atharokhoda. That’s the village directly across from our village jetty.’

‘Look! Can you see that? That’s the register. Your name’s in that. Do you remember what to say when he calls out your name?’

‘Pejen Sir!’

Patting me on the knee, he said ‘Correct!’

Sir fastened the string on the chair before sitting down. Did he know what had been happening here just a little while ago? The ones who were saying nasty things were like wet cats now. All silent. Suddenly Dulal took my hand and held it to his pocket. ‘Can you feel it?’

Marbles here too! I suppressed a laugh. He pressed his finger over his lips. ‘We’ll play a few rounds after school gets over.’

‘But I didn’t bring any.’

‘You’re an idiot – I wonder why you’re such a coward! Always keep the glass balls with you, I’ll give you some, so you can play if you feel like. So, it’s your first day today, didn’t you bring any money to buy snacks?’

I nodded to mean ‘no’.

Dulal looked glum. He said, ‘You could’ve bought some marbles with that money, played a round with that’

‘Oh heck!’

Then I said softly, ‘I think Ma would have given it to me if I had asked. But she was crying then.’

‘But why was she crying? Did you tell her something nasty?’

‘Oh nothing like that. She’s getting more sick. She thinks she’s going to die, that she won’t see me anymore. That’s why…’

Sir began calling out names. We were talking furtively. I wouldn’t have told Dulal. It was only because he suddenly asked me. Besides, he was the only one I knew here. But I had only whispered it to him. He was about to say something, and just then Sir said, ‘Who’s that talking?’

Several of the students turned around to look. I looked at them blankly, like a good boy. As if to say, it’s someone else who’s making trouble, not us, Sir.

After looking at us briefly, he continued calling out the names. As soon as he called out the last name, I sat up, startled. ‘Ratan Paramanik!’

It wasn’t anyone else, was it? My heart was beating fast. He called out the name again. ‘Ratan…’

As soon as I raised my hand, Sir asked, ‘Do you want to say something?’

‘That’s me. I’m Ratan Biswas, Sir.’

‘When did you get admitted?’

‘Yesterday, at the haat.’

‘Who admitted you?’

‘Sir, the one who’s dark-skinned. A bit plump. He had come to the shop for a haircut, it was that Sir.’

‘Then that’s you.’

‘But we are Biswas!’

‘That’s fine, what else could your surname be but Paramanik? Sit down!’ And saying so, he shut the register.

*

What a bloody cracked mirror!

Baba squinted his eyes and examined the hair at the back of the customer’s head. He wouldn’t notice even if someone stood beside him. He didn’t notice that I was there, either, or that I had even entered the shop. I called him softly, ‘Baba.’

He raised the pair of scissors from the head. ‘Could you learn properly? Sit. Just a bit more. Can you lift up the curtain at the door? It’s not sunny anymore.’

Baba ran his eyes over the hair for the last time. He asked, ‘How many books need to be bought? Have you written everything down?’

When there had been a lot of haircuts, there would be clumps of hair on his dhuti. My first day at school. Baba had been busy. If there was any more work at the shop, I could lend a hand.

Where on earth had Dulal vanished from the bridge? He hadn’t said a thing. Just ‘Go now.’

The customer was looking at himself again and again in the mirror. Turning his head sometimes, leaning forward sometimes. He said, ‘Can you hold the mirror at the back?’

Baba was moving the small mirror and showing him. This side and that side. ‘Hey, hold it properly! Why are your hands shaking?’

‘Here you go!’ Baba said solicitously.

‘Raise the mirror!’

Baba would have held up the mirror even if the man had not jerked his head like that! ‘Did you hurt yourself…’ Baba began.

‘What a bloody cracked mirror!’

Baba was silent. Such admonishments pained him. If only the man had asked me instead of Baba.

He was very annoyed. But did that mean he could fling the coins? Baba picked them up carefully. He said nothing. He simply heard it all. He examined the coins to see if they were in currency. As he looked at them, he asked me, ‘Did the Master-moshai ask you what you learned?’

Just like I had felt bad for Ma while leaving for school, I felt the same way for Baba now. I just kept gazing at him. He couldn’t see well. Ma knew that customers didn’t want to go to him because he was old. Perhaps there’d be a couple more customers if I went along.

He had a scar from the middle of his chest to below his navel. His abdomen had been cut open at the Calcutta Medical College Hospital for his digestive ailment.

Baba removed his glasses and wiped his eyes several times. ‘Did you write down the names of the books required?’

Why wasn’t I able to reply? Why was I staring at him blankly?

I remember an Urdu-speaking man had made Baba a pair of spectacles. It wasn’t just Baba – several people in the marketplace had them made. The man had sat all day under the jackfruit tree beside the Kali temple. I remember that when Baba returned home, Ma gazed at him for a long time, as if some stranger had entered. Baba asked, ‘What happened, my dear, can’t you recognise me?’

‘I’m just looking.’

‘What are you looking at?’

‘At the new person. With new eyes.’

‘I got the spectacles made. I was scared. What if I cut someone while running the razor over his face!’

‘Can you see clearly now?’

Baba didn’t reply at once. After a pause, he said, ‘It’s clear, but it’s also hazy. A lot of things suddenly appear large. That’s the only difficulty. It’ll be fine. After all, anything new has to be hazy for a while.’

Baba still had the same pair of spectacles. He didn’t wear them for long. He said that he couldn’t see properly if he did. When the shop was empty, he could see the marketplace and the people clearly.

Wiping his glasses, he said, ‘Do you want to eat something, Ratan?’

I wanted to. I’d go and fetch something. ‘Like to have shingaras?’

‘Will you get them at this hour?’

‘Shall I go to Makhan Kuri’s shop and have a look?’

‘Go. Get some if it’s available. Tell him my name. One for you and one for me.’

On credit yet again! I wanted to tell him, why buy on credit all the time, Baba? If there’s no money, I don’t want any. But I couldn’t say that. It was the first time he had asked me to buy something for him at the mention of food. Baba wanted to have it, too. So, like us, Babas too liked to eat!

As I ate the shingara I saw Ma holding the post and trying to step down from the verandah. She was unable to get her feet on the ground. She held onto the post. Baba asked, ‘Hey, what’s up, why did you put it all into your mouth? What’s the hurry?’

No. It couldn’t be said. Not even to Baba. If I did, he’d say, eat slowly. Finish eating and then go. But I didn’t have to say anything. Baba understood, I was going back home.

The marketplace was desolate now. Just a few people around. As soon as one went past the Kali temple’s jetty, there was Ode the blacksmith’s shop. It was so snug on wintry days. He sat bare-bodied in front of the fire as he hammered away at the iron. Needless to say, he didn’t wear a shirt in summer either, but I had never, ever seen Ode Kaka with a shirt on at any time of the year.